America's depression epidemic and the 'most dangerous woman in the world'

Red Meat For Mushy Moderates

It seems that every day we’re confronted with yet more evidence that America is unraveling, not just at the edges but at the seams themselves. Mass shootings seem to be a weekly occurrence, if not daily. We can blame it on the easy availability of military-style firearms and that scourge is clearly part of the problem.

But if we dig a little deeper, we see other contributing factors. It should be obvious by now that America is a very different place than it was 20 years ago, or even three and half years ago on the precipice of the pre-COVID era.

The epidemic of poor mental health afflicting our nation is often cited by those on the right when the issue of gun control is raised. Coming on the heels of tragedies such as the most recent mass shooting in Cleveland, Texas, these calls from conservatives seems more of an excuse not to pursue meaningful gun control policies than anything else. But that doesn’t mean the need to address our collective mental health is an empty suggestion from Second Amendment aficionados either.

I was struck by an op-ed this morning in the New York Times by Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy addressing the subject of loneliness, which is closely associated with mental health. Murthy described his own struggles with loneliness after his first stint as surgeon general had ended. Murthy had spent so much time at his job that he had neglected his friendships and, after he left his job, “felt ashamed to reach out to friends I had ignored.”

He also cites the story of a patient of his who worked in the food industry and led a modest life. After he won the lottery, Murthy’s patient quit his job and moved into a gated community.

Wealthy but alone, this once vivacious, social man no longer knew his neighbors and had lost touch with his former co-workers. He soon developed high blood pressure and diabetes.

Murthy reported that, “Even when I was physically with the people I loved, I wasn’t present — I was often checking the news and responding to messages in my inbox.” Loneliness has been on the rise in this country for some time, but has grown with the rise of social media and its false promises of making us feel more connected than ever.

The trend accelerated with the onset of the pandemic when most of us were told to stay in our homes and, even after the contagion receded, management told many of us we were to work remotely for the foreseeable future. The isolation hit older people even harder because of their increased risk of death by the virus.

Some have even argued that our epidemic of loneliness began with the rise in the 1960s of television, which encouraged otherwise good citizens to stay home in the evenings rather than go out with friends or participate in activities related to civic engagement.

According to a 2021 Harvard study, more than one-third of Americans report being lonely. That percentage rises to 61% among younger people (a cohort of heavy social media users) and 51% among mothers with young children. Officials say the consequences can be fatal: an analysis by the National Institutes of Health compared loneliness to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

I offer no solutions here. No one can, it seems — though Murtha suggests three modest steps one could take. The subject has been studied and written about by experts and even politicians such as former Republican Sen. Ben Sasse, who is now president of the University of Florida. Sasse wrote a book positing that loneliness and the fear resulting from it are major factors in “Why We Hate Each Other.” If true, Sasse’s theory could explain everything from political violence to mass shootings.

‘Dangerous’ or simply wrong?

It is time for teachers in public schools and others who advocated for keeping the schools closed for extended periods of time during the pandemic to come clean. I understand that during the early stages of the pandemic, there were lots of unknowns, vaccines had yet to be developed and closing the schools to in-person learning during the spring of 2020 was defensible — out of an abundance of caution, if nothing nothing else.

“Never let a good crisis go to waste,” quipped Winston Churchill as he was working to form the United Nations after World War II.

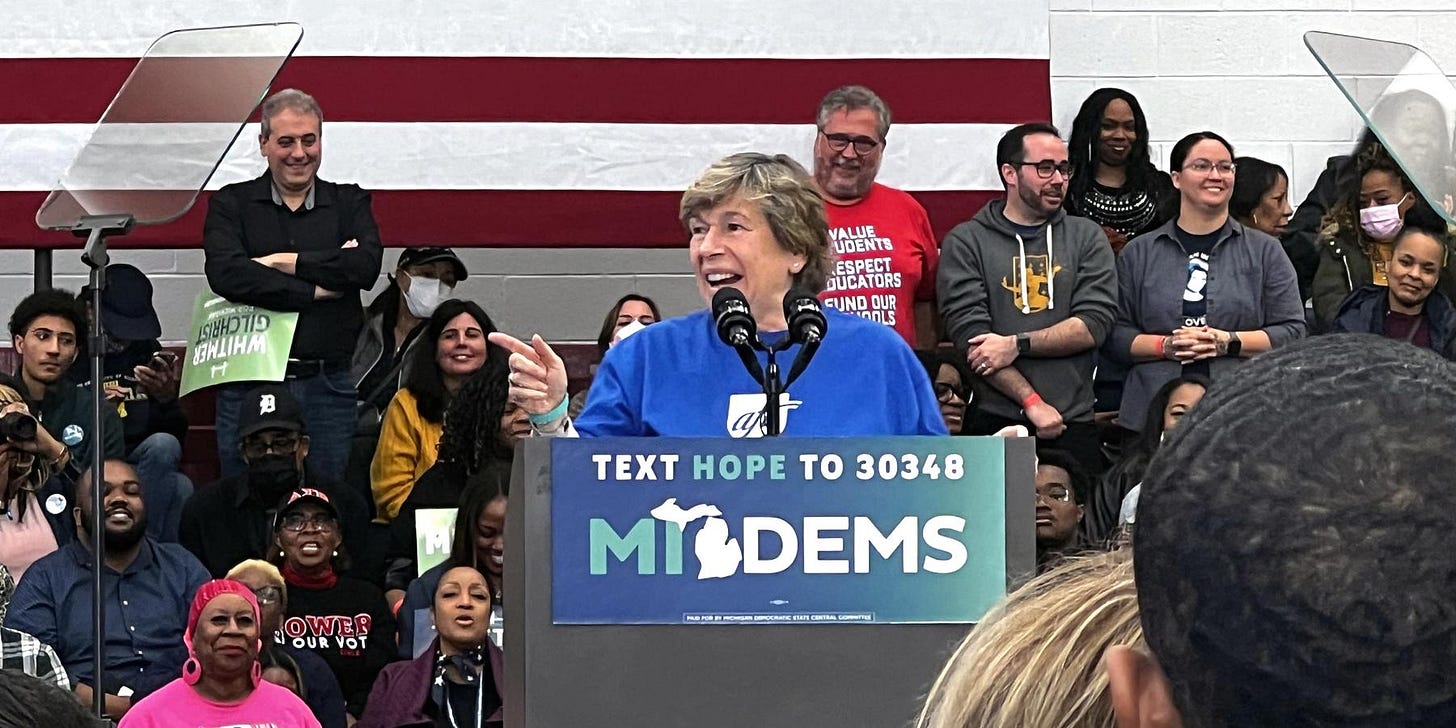

But that summer when the question of reopening in September came up, too many teacher unions objected. Randi Weingarten, who leads the American Federation of Teachers, came down strongly on the side of keeping schools closed, and used the pandemic as an opportunity to push for long-sought reforms and more money for schools, as a recent piece in the New York Times Magazine reports.

In the summer of 2020, I was two years from retirement and covering the Berkshire Hills Regional School District in western Massachusetts. The teachers union in the district objected to reopening to in-person learning because, it said, “The majority of teachers, support staff, related service providers, and paraprofessionals do not feel safe returning.”

The superintendent had originally proposed a hybrid model, but reversed course to remote-only a couple of weeks later after strenuous objections from the union. The board of education heard from lots of parents who took exception to the decision, especially those whose children had special needs.

The teachers’ reaction struck me as odd. Teachers are always telling us — and rightly so — that great teachers are indispensable to education and that they can literally change lives. To me, that makes them essential workers. Even in the early stages of the pandemic when most people were told to stay home, exceptions were made for these “essential workers” such as grocery store employees, healthcare workers, police, fire and other first responders. It struck me that by taking such a militant position, teachers unions were suggesting their members were less essential than, say, a cashier at Target.

For obvious reasons, it was a relatively easy position for the union to take. After all, the district has a guaranteed revenue stream. The money will keep coming in from taxpayers whether the schools fully reopen or not. The region’s private schools, on the other hand, reopened, albeit cautiously.

This was predictable. Unlike public schools, private schools, if they had continued to offer remote-only learning, would have faced a revolt from parents who would either demand tuition refunds or transfer their children to another school with in-person learning, resulting in lay-offs of faculty and staff at the remote-only school.

Beyond damaging their relationship with wounded parents who had to continue to pay their taxes anyway, the teacher unions in the public school district faced negligible consequences. Meanwhile, schools in more conservatives states reopened in the fall. Schools in many European nations also reopened to in-person learning, with appropriate caution.

There was never any real data to support the idea that schools were superspreader environments. Still, many U.S. districts remained closed to in-person learning well into 2021, even after vaccines were available. About half of American children lost at least a year of full-time school, according to Michael Hartney of Boston College.

The ensuing learning loss for the affected children was devastating. They lost significant ground in most subjects and those hardest hit were children of color — specifically Black and Latino. Depression and suicide rates went up and the American Academy of Pediatrics declared a national emergency in children’s mental health.

Weingarten is not, as former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo branded her her, “The most dangerous person in the world.” Those were the demagogic words of a man who wants to be president so badly that he’s willing to slander a union boss just to please Trump Nation.

Still, it’s time for Weingarten and educators who objected to the full reopening for the 2020-21 academic year to admit they were wrong. I personally would forgive them. After all, I’ve made a few blunders over the course of my career, too. But I will not elaborate …

Murphy weighs in

My own U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy weighed in the “loneliness epidemic” yesterday. Read it here in the New Haven Independent.

Hi Wayne. Good to hear from you. I don’t think the unions have “destroyed the education system,” but I do think they resist reforms and other common sense measures that might improve outcomes. And they protect bad teachers but that’s what all unions do. Hope all is well down south. -TC

For the record, the school where I teach was open by late August of 2020, and teachers were in their classrooms every day (like many others in Connecticut, a blue state). The local teachers' union did not protest. I think we must be careful in painting teachers and unions in Connecticut with the same broad brush as we paint teachers and unions in other states. To be honest, I've never been a big union guy, but I also understand the need for unions in education. As for Connecticut, the CEA has much less influence than many naysayers claim. Not to mention, teachers in Connecticut cannot strike; it's against the law due to the arbitration process in place. So, I would just say beware "hasty generalizations" when discussing "teachers in America."