Another respite from politics:

Note: I love Mike Allen’s morning email. I know … there are plenty of people who don’t like Axios’ “smart brevity” approach — otherwise known as “saying more with less” — but sometimes it really connects with me and I learn a lot from it. You can subscribe to it free of charge here.

One item from Aug. 6 really caught my eye because I’ve been pondering it for awhile — essentially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s a subject that just about everyone has an opinion on because … well, it touches all of our lives.

Axios’ assessment is that we are seeing “backlash” against the practice of tipping in America. That might be overstating it a bit, though there is data suggesting that large numbers of American consumers are experiencing what I would call “tipping fatigue.”

Why? It looks like at the onset of the pandemic, there was a surge in tipping for a couple of reasons: 1) We seldom went out to eat or we engaged less in tip-related commerce, so we had more money to spend when the situation required a gratuity. 2) We were grateful for the restaurant workers, delivery drivers and other essential employees for braving the pestilence and being there when we needed them, so we opened our wallets.

Paradoxically, a Bankrate survey from May 2023 found that 66% of Americans have a negative view of tipping. Nevertheless, 65% say they always tip servers, down from 73% last year and 77% in 2019, the year before the pandemic. So it actually appears that Americans are tipping less than we used to even before COVID.

Why? I think the practice has gotten out of hand. Whereas tipping used to be confined to those who served us up-close and personally (waitstaff, bellhops, cab drivers) and offered good service, it seems that the cast of those who deserve tips has expanded exponentially over the last few years.

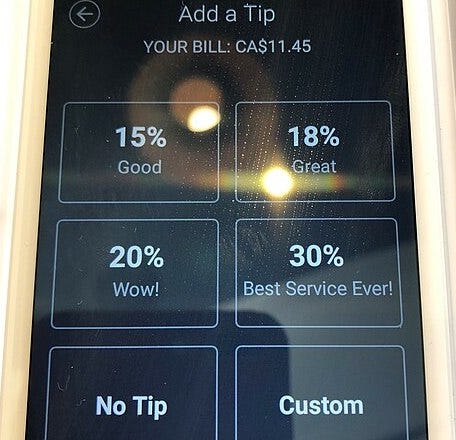

New technology has also made it easier to ask for gratuities or to prompt customers to tip. Walk into a sandwich shop or coffee house and you’ll find a tip jar next to the register. Or if you’re paying via credit card, the touch screen will offer you the option of tipping 15, 20 or 25% or more — a virtual tip jar. It’s not clear who will get the dough, but it’s safe to say that it gets divided up at the end of the day between front-of-house staffers, whether they’re doing a good job or not.

The self-serve car wash I use is otherwise excellent, but when I emerge from the sudsy storm and am ready to drive away, I’m accosted by a young woman with a towel who insists on drying off my car. I hesitate to say no because she is dressed in little more than rags. So I wait patiently for her to finish and throw her a few bucks. It reminds me of when I was stopped to get onto the 59th Street Bridge some 35 years ago in Manhattan and was approached by a squeegee guy. You really can’t say no when you’re stopped and someone is standing next to your driver-side window.

According to Axios Charlotte, virtual tip jars are cropping up at movie theatre concession stands. Now that would be an easy ask to swat away. The price of concessions at the movies has long been outrageous. Asking (demanding?) tips in the land of $10 popcorn? That would, as Johnny Carson was fond of saying, “go over like a pregnant pole-vaulter.”

Though I have never experienced this personally, Axios adds that, “Vendors offering pricey services who you might not typically tip and who might not even expect a tip — like wedding photographers and HVAC technicians — are using payment software that requests tips, leaving consumers confused about whether there are new rules.”

Indeed, tipping etiquette seems mostly subjective. There are the obvious recipients (the van driver at the park-and-fly; the barber; the Uber driver), but there are also judgment calls. A few years ago, my daughter texted and told me her 12 year-old Honda Pilot had finally dropped its transmission. I called a garage to tow it to our mechanic, who had it had it hauled away to a junk yard.

Question: do you tip a tow-truck driver? How about the kid at Walmart who wheels that new Samsung flat-screen out to your car? I tipped in both cases (the kid was thrilled; the tow truck driver shrugged).

Another explanation for the expansion of the gratuity culture is that wages in tipped jobs haven’t kept up with inflation and businesses are looking to customers to make up the difference. But how can we really know what we should do if we don’t have a definitive list of what constitutes a tipped job?

Those working in obviously tipped jobs (wait staff, the pizza delivery guy) have long had a much lower minimum wage than those who work other service jobs. Most states in New England now have a $15 per-hour non-tipped minimum wage, or close to it. For obvious reasons, the tipped minimum wage is considerably lower. If the tipped minimum wage rises, as many are demanding, it stands to reason that the menu cost of your meal will rise accordingly.

P.S. In some cultures outside North America, tipping is considered uncouth or it is not expected. I spent two weeks in South Korea and we were told by our tour guide that tipping is not customary. Someone else we met in Seoul told me Korean workers are insulted by tipping, as if to say, “You don’t need to bribe me to receive good service. It’s what I do.”

* * * * *

My latest column for CTNewsJunkie went live yesterday morning:

Too Many Actors, Not Enough Work; Strike’s Implications for Connecticut

* * * * *

As a follow-up to my series on ethical problems at the Supreme Court of the United States, I am pleased to report that ProPublica has published yet another investigative story on Justice Clarence Thomas:

Former U.S. Attorney for Alabama Joyce Vance isn’t happy about it:

And Andy Borowitz offers his own thoughts in the New Yorker:

Clarence Thomas Hikes Price of Supreme Court Decisions to Keep Pace with Inflation

Citing “unfortunate economic realities,” … the jurist disclosed his new rate card in a mass e-mail sent to more than a hundred super-donors.